Well, given that agents stand guard over the watchtower that protects the entrance to the fortress of publication, what they say goes. Without them you will not get a foot on the drawbridge; the portcullis will never be raised, no matter how much you shout at the thick stone walls. They all say they are on the lookout for new writers to excite them – to elevate some poor aspiring writer amongst the many on the outside all hoping to access the London literary citadel. And there are so many millions on the outside: too many people writing books, which quite frankly aren’t very good. It is therefore hard for even superb, new books to surface above the vast sea of mediocrity. The agent becomes a necessity.

But the focus of agents by necessity is on the inside of their castle – first and foremost they have to make money from their existing list of authors. That is how they pay their bills, buy their Prosecco. That means spending time and effort schmoozing with publishers and promoters to get those projects onto the mass market – selling tens of thousands on the shelves of Tesco and the newsagents at railway stations and airports.

They all claim to be in favour of diversity, but they cannot easily take a risk with something that is not like something else that has already sold well, or with a book by an unknown whose very name does not automatically generate interest in our celebrity-obsessed society. If you regularly appear on TV, your new children’s book / romance / kiss-and-tell is a shoo-in, whether it is any good or not. The book has to be a good bet to sell to the thirty-something, tube-riding, Pret A Manger-eating, aspirational female.

So, agents become the arbiters of taste. The advice that comes down from on high is advice – not on what makes for good literature – but what they might best be able to clinch a big deal on with publisher. Do they amount to the same thing? Sadly not.

An agent will spend a small proportion of their time looking at submissions. They will rarely read past the first page – if they even get as far as picking the manuscript up. They rarely waste their valuable time in correspondence, or the basic courtesy of a reply to an inquiry letter. So, what is the advice for that crucial first page? They all say they have to be grabbed immediately by what they read; they want to be in the story straight away. These are not people who are fond of a long slow chat-up or gentle foreplay. They want their pants down on page one. George Eliot would not get her novels looked at if she was around today. Adam Bede has one of the best introductions in English literature but it is long and slow and descriptive and you have been reading some time before anything much happens. It leads the reader gently by the hand rather than thrusting them rudely up against the wall.

An intelligent reader of these modern high-octane novels, soon tires of the formula, of immediate peril, of tension being cranked up, of being psychologically manipulated by an author who is writing to a recipe. Louise Doughty’s brilliant novel Stone Cradle is skilfully crafted, is languid. It is as near perfect as a novel can be. Yet it is the Alton Towers-ride, nauseating rush, of Apple Tree Yard that is popular and sold in large numbers.

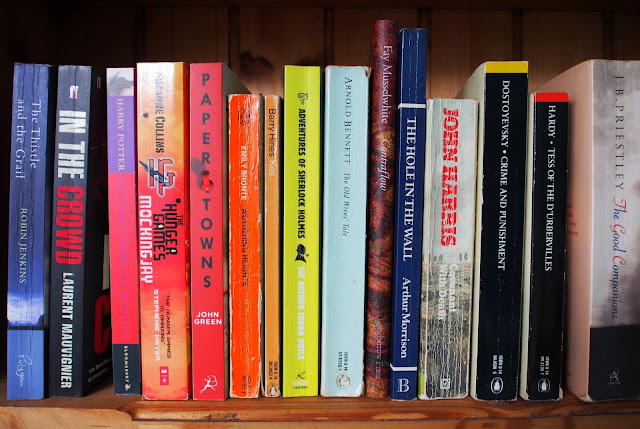

What is going on? It is all symptomatic of an infantilization of society. Those who read Harry Potter, who proudly announce they favour YA fiction as a genre. Thinking is a trait to be discouraged – in fact, how often do you hear it proudly rejected – when you tell someone about a great book and they reply that they don’t read books but have seen the film because it requires nothing from them. It is mere passivity. Who but a crank would read Tolstoy these days? Anna Karenina is a terrible book by modern standards – badly plotted, dreadfully paced, parallel, largely unrelated stories (of Levin and Anna), far too wordy and full of description that does not serve the plot. And the title is just boring and says nothing about what the book is about.

As authors we are told we are competing not with other authors but with other forms of entertainment. What hope then for an author who wants to write intelligent adult fiction in a world where there are fewer and fewer grown-ups? Where people in their 20s, 30s or 40s go and watch Star Wars without even the excuse of taking their kids with them. Grown-ups who still drink fizzy pop, who prefer their coffee milky and caramelly, who dress like American teenagers, and who can’t be bothered to work out how to vote so trip out the mantra that “they are all the same.” That is of course the point. Large corporations want brand loyalty, they need you to be a slave to your smartphone, to upgrade it every year, and it suits governments who don’t want you to think for yourself – they want you to leave them to get on with it otherwise they might lose power and risk the overly large slice of the cake they and their friends enjoy.

If that has depressed you, take heart. Just as indie-music kicked down the doors of the stronghold of the likes of the EMI, RCA, Polydor and CBS in the late 70s, so there are more and more small and independent publishers out there who are not tied to huge print runs, who are fleet of foot, not tied to London, who run a tight budget and care more about great literature than shovelling stodge down the throats of the masses. The big publishers like to regard themselves as guarantors of quality, but as with music in the 1970s, they no longer have such a monopoly. The big publishers still have a stranglehold on the shelf space and tablespace in big bookshops, but readers are finding other ways to discover a more varied, richer reading diet.

No comments:

Post a Comment